“We will soon be facing

a post-growth economy”

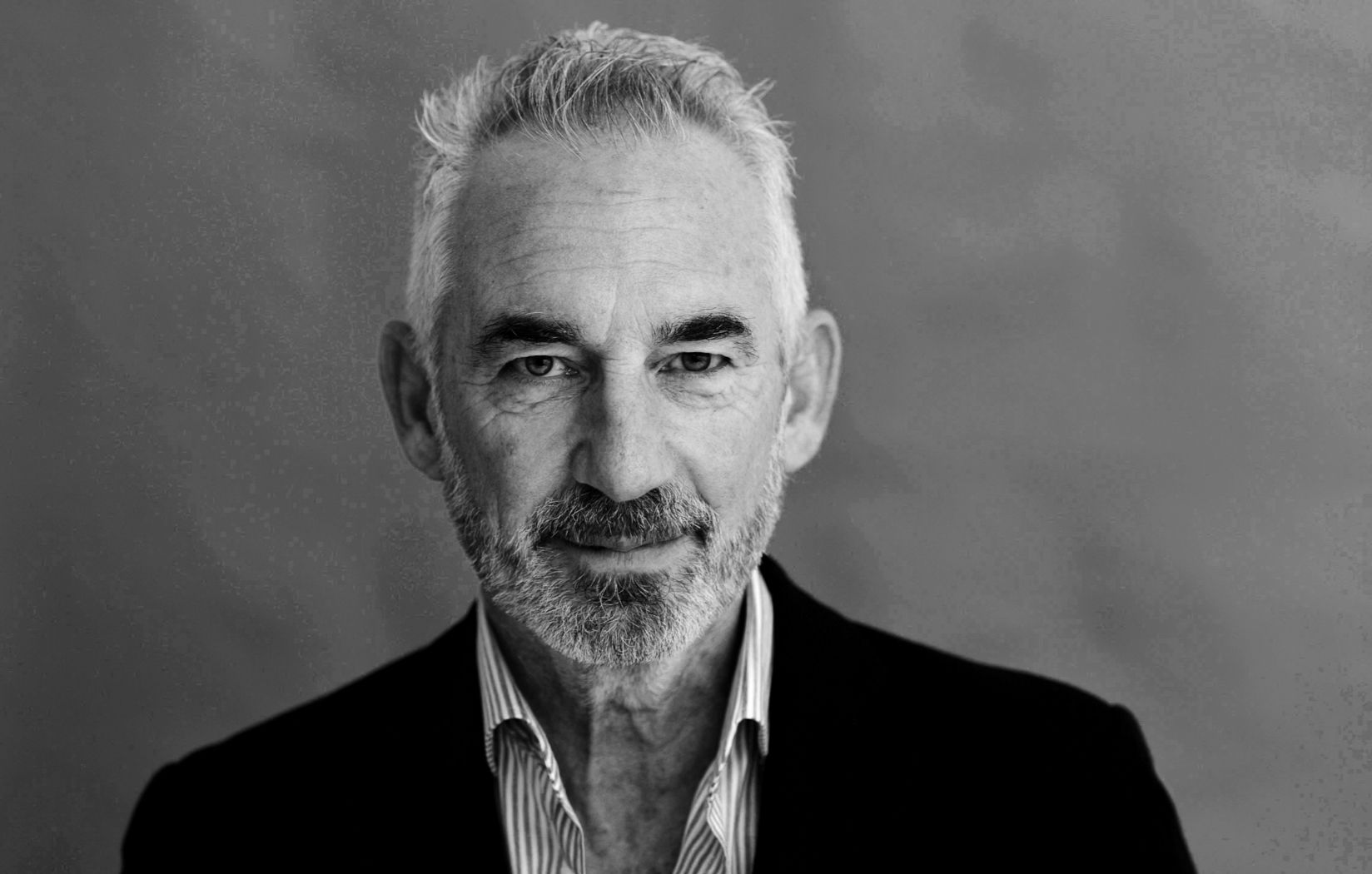

The relationship between sustainability and economics needs to be re-evaluated in the future. In this interview, British ecological economist Tim Jackson explains his idea of post-growth economics and what it means for businesses.

Professor Tim Jackson is an ecological economist and Director of the Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity (CUSP) at the University of Surrey in England. CUSP is a multidisciplinary research center that aims to understand the economic, social and political dimensions of sustainable prosperity. In 2009, he published his controversial and groundbreaking book Prosperity without Growth, which has been translated into 17 languages.

Professor Jackson, you have been researching the context between sustainability and the economy for decades. What do you mean by post-growth economics?

Jackson Post-growth economics is a way of thinking about what might happen when GDP growth is no longer our primary indicator of success. One of the main reasons for doing that, apart from the environmental and social reasons, is that the growth rates that economists and politicians have come to expect have been slowing down, not just since the financial crisis, but actually over the last roughly half a century. The rates in advanced economies have slowed down from around about 4% or 5% per year in the 1960s and 1970s to around 1% a year across the OECD nations at the moment. Even before the pandemic, that was the trend. The implication is that we will soon be – if we are not already – living in a post-growth economy, like it or not. To me that means we need an economics that takes seriously the idea that prosperity is not just about growth. It’s also about health, about relationships, about one’s community and about having some sense of purpose in life.

You wrote the growth-critical bestsellers “Prosperity without Growth” and ”Post Growth”. What do you say to people who claim that global emergencies such as the banking crisis in 2008 or the corona pandemic since 2020 cannot be overcome without growth?

Jackson I would say that our difficulties in dealing with those crises were, at least to some extent, because of the primacy that we give to economic growth. I believe the financial crisis itself can be seen as a consequence of our obsession with economic growth. It was because of this obsession that we deregulated finance. And in doing so, we undermined stability. In a sense, the collapse of the financial sector was as much a consequence of our pursuit of growth as it was of our failure to deliver that growth. If I’m right then it means we need to be much more nuanced in our solution space when we’re faced with global crises. We need to understand where those crises came from and what sorts of recovery are necessary. Our response to the financial crisis invoked a damaging austerity which undermined social welfare. When the pandemic hit, our health systems were already weakened from ten years of underinvestment. The pandemic was clearly a ‘special case’. From one day to the next, we basically turned off most of our economic activity. We did it to protect the health of citizens. We put health above wealth – and that was the correct decision at that point. Do we want to recover some of that economic activity? Yes, of course we do, because people’s livelihoods depend on it. Equally, in the poorest countries in the world, there is still a need to increase economic activity in order to improve people’s lives. That’s not ruled out by what I’m calling a post-growth approach. What is ruled out is the idea that the solution to those kinds of problems can come purely through pushing growth as fast as possible, as we did in the past. The simple mantra of economic growth at all costs cannot provide the solution to some of those problems. Our fixation on productivity is an integral part of our obsession with growth. But we have to think in a more nuanced way about what really matters. We can start by building a broader concept of prosperity, where the most important economic activities have nothing to do with the pursuit of abstract growth. Instead, they depend on care, craft and creativity: the very things that make our lives valuable and worth living.

Why is sustainable management a meaningful option for companies, despite the fact that they are actually under constant pressure to make a profit and act in an economically expedient way?

Jackson There tends to be a conflict in the way companies are organized: between the pursuit of profits and the goals of sustainability. This happens because a company’s revenues need to satisfy three competing demands: the wages and salaries to be paid to people working in the company; the dividends to be paid to shareholders; and the investment that needs to be made in order to achieve future economic success or to achieve ecological sustainability. Those variables are in conflict with each other in the forms of corporate structure that we are most familiar with. It seems to me that recognizing that conflict is really important. We have to move beyond Milton Friedman’s dictate that ‘the business of business is business’ and that profit is the only legitimate output indicator for a company. We’ve seen how that approach is a recipe for disaster. Society is beginning to say that a company must always have a very keen eye on its own sustainability. So, in relation to climate change, for example, companies are now beginning to internalize the idea, and rightly so, that they must think about the transition to a net-zero-carbon company. Sustainability and the transition to net-zero no longer means just a kind of social and environmental branding for the company. Nowadays it’s critical to the material existence of that company in the long run.

What will be required of companies in the future in terms of sustainability and how should they act?

Jackson I think that the primary lesson for companies today is that by embracing a vision of the future in which sustainability is front and centre of your purpose, you have an advantage, both in relation to other companies, but also in relation to your own viability as a company. Being a laggard in relation to sustainability is likely to risk damaging your so-called social license. In other words, failing to take sustainability seriously represents a material risk to your company. So the way ahead for companies is both to internalize the vision of a sustainable company and to be proactive about sustainable management practices.

What is the role of business in your world where balance, not growth, is the essence of prosperity?

Jackson A world where business is oriented toward having more and more is a recipe for disaster. Particularly in a world where human health is about balance rather than growth. Because you’ve got business incentives pushing in the direction of relentless expansion while human health, and the human body itself, needs to be able to remain in balance. The concept of balance should therefore be a boundary condition for our idea of progress. Now, what does that mean for businesses? First of all, perhaps, it means establishing where the limits are. Even though we know where some of those limits are, say, with climate change, we’re not integrating them into policies in the way we need to. The establishment of limits is a vital step in being able to look ahead to the way the economy is going to develop outside of this pathological dynamic. The second kind of solution space is about fixing the economics. It is about beginning to design economics itself and economic institutions that reinforce long-term interests. This has some very clear implications for business – for example, how you strategize investments, how you measure the performance of investments or how you shift the balance of investment toward long-term goals in your production sector. The third solution space is about changing social logic. People as consumers are locked into specific patterns of behavior. If you need growth, you need people to go on buying more. What we’re living in is a system designed to kick start and stimulate consumption. Recognizing that, we have to systematically shift back to achieving a balance. For businesses, this means going beyond the mass production and consumption of material products and focusing value added on quality and on meeting the need for human services.